In the lush, waterlogged rice fields of northern Vietnam, an ancient art form emerges from the mist—a vibrant spectacle where carved wooden puppets dance atop liquid stages. Water puppetry, or Múa rối nước, is a tradition steeped in the rhythms of agrarian life, where farmers turned entertainers conjured myths and mundane joys from the very waters that nourished their crops. For nearly a millennium, these performances have been a bridge between the earthly and the divine, a folk theater birthed by monsoon floods and communal ingenuity.

The Red River Delta, with its labyrinth of paddies and ponds, is the cradle of this art. Villages like Đào Thục and Nguyên Xá became custodians of the craft, building bamboo-screen theaters in flooded fields. The puppeteers, waist-deep in water behind a split-bamboo curtain, manipulate lacquered figures using submerged poles and strings. Dragons spew fireworks, ploughmen chase mischievous foxes, and Quan Âm, the Goddess of Mercy, glides across the waves—all to the dissonant symphony of wooden bells, two-stringed đàn nhị lutes, and the nasal wail of kèn oboes.

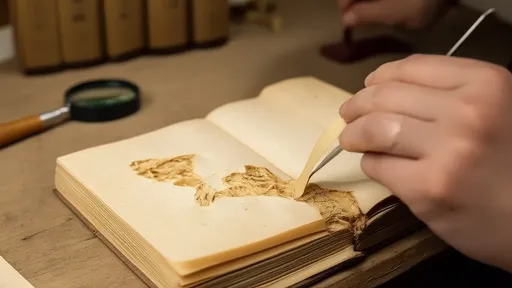

What makes Vietnamese water puppetry transcendent is its alchemy of elements. Water isn’t merely a stage; it obscures mechanics to create magic, amplifies splashes into dramatic punctuation, and mirrors puppet movements in rippling doubles. The materiality matters too—figures are carved from fig wood, buoyant yet resistant to rot, their joints articulated to mimic the angular grace of temple reliefs. Traditional stages even incorporated phù điêu (floating carvings) that rose from the water like miniature pagodas.

Colonial-era anthropologists once dismissed it as "peasant vaudeville," but water puppetry carries coded histories. Scenes like Lê Lợi Returns the Sacred Sword—where a golden turtle reclaims Excalibur-like blade from the 15th-century king—are nationalist allegories. Others, like the ribald Frog Catchers skits, preserve pre-Confucian bawdiness. UNESCO recognized this duality in 2021 by inscribing it as Intangible Cultural Heritage, noting its role in "sustaining communal memory through hydrological theater."

Modern troupes like Thăng Long Water Puppet Theatre have globalized the form, but purists argue electric lighting and concrete pools sterilize the art’s essence. Yet even in slick Hanoi productions, when the dragon boat races begin, water arcing over the first row of spectators, something primal remains—the sense that these splintered reflections of village life still hold up a mirror to Vietnam’s liquid soul.wayang kulit

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025