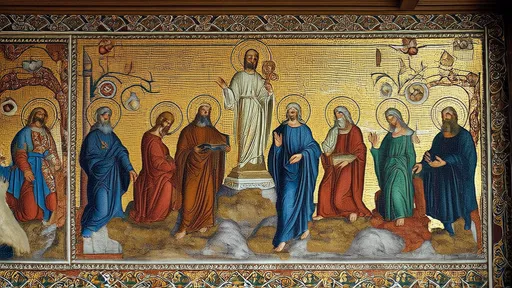

The golden glow of Byzantine mosaics has captivated art historians and spiritual seekers alike for centuries. These intricate works, composed of countless tiny tesserae, transform sacred spaces into shimmering visions of the divine. At the heart of this luminous artistry lies a material both humble and extraordinary: gold-glass tesserae. More than mere decoration, these golden fragments embody a sophisticated theological vision that merges craftsmanship with cosmology.

Walking into the Hagia Sophia or the Basilica of San Vitale, one is immediately struck by how light behaves differently in these spaces. The mosaics don’t simply reflect light—they seem to generate it from within. This effect was achieved through a painstaking process where glassmakers sandwiched gold leaf between two layers of glass, then cut the material into small cubes. When set at slight angles in mortar, these tesserae captured and multiplied ambient light, creating the illusion that the walls themselves were radiant. The technique was no accident; it was a deliberate attempt to visualize Neoplatonic ideas about divine emanation, where material beauty served as a conduit to the immaterial.

The theological implications were profound. In Byzantine thought, light wasn’t just a physical phenomenon but a metaphor for God’s uncreated energies. Writers like Pseudo-Dionysius described divinity as "the luminous darkness," an ineffable presence that could only be approached through symbolic representation. Gold-glass mosaics became the perfect medium for this apophatic theology—their flickering surfaces simultaneously revealed and concealed, much like the divine mysteries they sought to portray. A mosaic of Christ Pantocrator, for instance, wasn’t meant to be a literal portrait but a window into transcendent reality, where the play of light across the face suggested both immanence and otherness.

Artisans elevated their craft to theological discourse through intentional material choices. The gold’s purity echoed biblical descriptions of heavenly Jerusalem, while the glass’s fragility mirrored human mortality. Some scholars note how tesserae surrounding Virgin Mary figures often contained cobalt blue glass mixed with gold—a visual paradox representing her dual nature as earthly mother and Queen of Heaven. Even the irregular placement of tiles carried meaning; the slight gaps between tesserae created kinetic effects that reminded viewers of the living, dynamic nature of spiritual truth.

This sacred technology reached its zenith during the Macedonian Renaissance, when mosaicists developed techniques to modulate gold’s intensity. By varying the thickness of the glass layer above the gold leaf or using colored underlays, they could make certain areas glow like fire while others remained subdued. In the Deësis mosaic of Hagia Sophia, this gradation creates an arresting psychological effect—Christ’s face appears to shift between compassion and judgment depending on the viewer’s position and the time of day. Such sophisticated manipulation of light and perception suggests that Byzantine artists understood optics with an almost scientific precision, centuries before Western Renaissance painters rediscovered chiaroscuro.

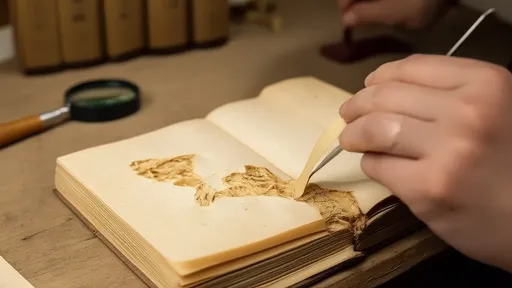

Modern conservation efforts have revealed surprising details about these medieval light experiments. Advanced imaging shows that mosaicists sometimes layered silver foil beneath gold to enhance reflectivity in dimly lit areas of churches. In Ravenna’s Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, restorers discovered that certain background tesserae contained minute bubbles—an intentional imperfection that scattered light to create a celestial "twinkling" effect during candlelit vigils. These findings confirm that Byzantine artisans weren’t just decorators but theological engineers, manipulating matter to provoke spiritual experience.

The legacy of Byzantine gold-glass mosaics extends far beyond their historical period. Contemporary artists like Hiroshi Sugimoto and James Turrell cite them as early examples of immersive light art, while Eastern Orthodox churches continue the tradition in new constructions. Perhaps most remarkably, these works still communicate their original intent across centuries; the golden fragments continue to whisper about a light that no darkness can overcome, making tangible the Byzantine belief that beauty was not merely aesthetic but salvific.

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025