The flickering glow of celluloid film has shaped our collective memory for over a century. Yet beneath the romantic veneer of analog cinema lies a silent crisis—films dating from the 1890s to the 1950s are disintegrating at an alarming rate due to chemical instability. Archivists now wage a desperate battle against time to preserve these cultural artifacts before they turn to dust.

Cellulose nitrate, the earliest transparent plastic film base, contained the seeds of its own destruction. Highly flammable and chemically volatile, this material was phased out by 1951—but not before leaving behind a legacy of unstable films that now decompose in vaults worldwide. As nitrate breaks down, it emits nitric acid gases that accelerate the decay process, causing the film to warp, bubble, and eventually crumble into a fine powder resembling cigarette ash.

Its successor, cellulose acetate (so-called "safety film"), proved equally problematic. Beginning in the 1990s, archivists noticed an alarming pattern—acetate films from the mid-20th century were developing a sharp vinegar smell as the plastic base underwent hydrolysis. This "vinegar syndrome" causes shrinkage, embrittlement, and eventually renders the film unprojectable. The chemical reaction creates an autocatalytic effect where degraded films speed the decay of neighboring reels.

The human cost of this decay becomes tangible when handling film cans from Hollywood's Golden Age. Archivists report opening sealed containers to find reels fused into solid bricks of celluloid, their emulsion layers welded together by decades of chemical breakdown. Early color films face particular vulnerability—the dye-transfer Technicolor process used until the 1960s fades unpredictably, leaving some preservationists to work with what they call "ghost images" of original cinematography.

Climate-controlled storage can slow but not stop this deterioration. The ideal preservation environment—maintained at 35°F with 30% relative humidity—merely buys time for the expensive process of film-to-film copying or digital scanning. Even under perfect conditions, nitrate film has an estimated lifespan of just 100-150 years before complete decomposition occurs.

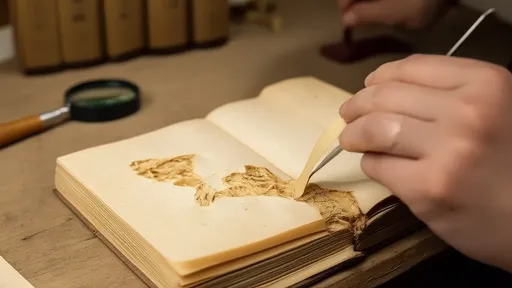

Modern preservation techniques combine forensic science with digital wizardry. At the Library of Congress's Packard Campus, specialists use spectral imaging to recover detail from shrunken film frames. Other institutions employ liquid gate scanners that temporarily fill film scratches with a refractive fluid during digitization. For severely degraded reels, conservators sometimes soak the film in plasticizer solutions to temporarily restore flexibility for a single transfer pass.

The economic realities of film preservation present another hurdle. While scanning a two-hour feature film in 4K resolution can cost $80,000-$120,000, archivists note this represents just 20% of the total preservation cost when including physical stabilization and metadata cataloging. With an estimated 80% of silent films already lost and half of all films made before 1950 at risk, funding remains perpetually inadequate.

Some of cinema's most pivotal works exist in precarious states. The original camera negative for Metropolis (1927) was cut apart and scattered across archives before partial reconstruction. Hitchcock's early silent films survive only in nitrate prints actively degrading in European collections. Even relatively recent films like Scorsese's Raging Bull (1980) required extensive photochemical rescue when the original negatives began fading.

Beyond Hollywood, the crisis affects global cinema equally. India's extensive film heritage—including early talkies like Alam Ara (1931)—faces tropical climate challenges. Soviet-era films stored in inadequate facilities show advanced vinegar syndrome. Even in climate-controlled vaults, color fading plagues Japanese masterpieces like Kurosawa's Ran (1985).

The philosophical debate surrounding film preservation continues to evolve. Purists argue photochemical preservation maintains the medium's material authenticity, while others champion digital migration as the only practical solution for mass salvation. This tension plays out in restoration labs daily, where technicians balance historical accuracy with the urgent need to salvage content.

As the chemical clock ticks, archivists work with diminishing resources against irreversible loss. Each rescued film represents not just entertainment preserved, but cultural memory sustained—a fragile ribbon of celluloid connecting past and future audiences in the flickering light of projection.

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025