The Art Nouveau movement, which flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, left an indelible mark on the world of decorative arts. Among its most enduring legacies is the intricate ironwork that sought to replicate the organic beauty of plant tendrils in metal. This fusion of nature and industry resulted in some of the most exquisite architectural and design elements of the era, transforming gates, balconies, and even street lamps into flowing, botanical masterpieces.

The Origins of Art Nouveau Ironwork

Emerging as a reaction to the rigid formalism of academic art and the industrial revolution's mass-produced aesthetic, Art Nouveau celebrated the curvilinear forms found in nature. Architects and designers like Hector Guimard in France and Victor Horta in Belgium turned to wrought iron as a medium capable of capturing the delicate yet dynamic qualities of vines, stems, and blossoms. The material's malleability when heated allowed artisans to create sinuous lines that seemed to grow naturally from the structures they adorned.

What set this movement apart was its holistic approach to design. Ironwork wasn't merely an afterthought but an integral part of buildings and interiors. The famous Paris Metro entrances designed by Guimard demonstrate how functional elements could become works of art, with their cast iron tendrils forming graceful canopies that appeared to sprout from the pavement.

Techniques Behind the Botanical Illusion

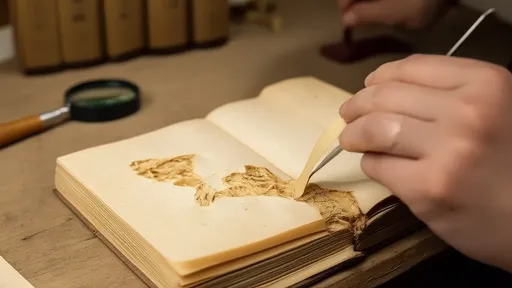

Master blacksmiths developed specialized techniques to achieve the fluid quality that defined Art Nouveau ironwork. The process often began with detailed sketches of actual plants, which were then abstracted into flowing designs. Artisans employed both traditional forging methods and innovative approaches like hot twisting, where red-hot iron bars were wrung like wet cloth to create spiral patterns reminiscent of climbing vines.

The finishing processes were equally important. Many pieces received patinas that mimicked the coloration of actual vegetation, with greens, browns, and even touches of gold creating a lifelike effect. Some workshops experimented with combining iron with other materials—glass inserts could represent dewdrops on metal leaves, while copper inlays added contrasting colors to suggest different plant species.

Regional Variations in Floral Ironwork

While the movement was international, distinct regional styles emerged in how artists interpreted plant forms through iron. In Barcelona, Antoni Gaudí took the concept to its logical extreme, with the wrought iron gates of Casa Vicens appearing almost like a three-dimensional botanical drawing frozen in metal. His work incorporated local Mediterranean flora, with palm fronds and orange tree blossoms becoming recurring motifs.

Meanwhile, Viennese designers of the Secession movement created more geometric interpretations of plant life, resulting in ironwork that balanced organic inspiration with structured composition. The Glasgow School, led by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, developed a unique vocabulary of stylized roses and elongated stems that appeared in both architectural ironwork and interior metal fixtures.

The Legacy of Nature in Metal

Today, these iron tendrils continue to captivate as they weather and patina with time. Conservation efforts across Europe aim to preserve these delicate metal gardens, with restorers often consulting botanical references to ensure authentic repairs. Contemporary metal artists frequently draw inspiration from these techniques, adapting them to modern materials and contexts while maintaining that essential connection to natural forms.

Museums dedicated to decorative arts invariably feature sections on Art Nouveau metalwork, where visitors can appreciate how these craftsmen managed to make cold iron appear to grow, twist, and bloom. The movement's emphasis on handcraft in an increasingly mechanized world resonates strongly with today's maker culture, making these century-old designs surprisingly relevant to current design discourse.

From the grand entrance gates of Brussels townhouses to the delicate floral stair railings in Prague apartments, the metal tendrils of Art Nouveau continue to enchant. They stand as testament to an era when industrial materials bowed to natural inspiration, and functional objects became vehicles for artistic expression. The next time you pass an old building with curling ironwork, look closely—you might just see where the metal ends and the illusion of growing plants begins.

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025