The art of Japanese lacquerware represents one of the most exquisite traditions in decorative arts, where time itself becomes a tangible material in the hands of master craftsmen. Among these traditions, the technique known as tsuikin or "stacked lacquer" stands out as particularly extraordinary - requiring not just skill and patience, but what can only be described as a lifetime commitment to the perfection of layered beauty.

In the quiet workshops of Wajima, Kanazawa, and Kyoto, artisans continue practicing methods that trace their origins to China's Tang Dynasty before being refined to extraordinary levels during Japan's Edo period. The process begins with selecting the finest urushi sap from lacquer trees - a material so temperamental it requires specific humidity conditions and can cause severe allergic reactions until the craftsman develops immunity through years of exposure.

The foundation determines everything. Master lacquerers start with a base material of wood, bamboo, or sometimes even paper-mâché, preparing it through weeks of careful sanding and priming. Each layer must cure perfectly before the next can be applied - a single bubble or speck of dust ruining months of work. The true magic begins when the artisan starts applying the colored lacquer layers that will eventually be carved into intricate designs.

What distinguishes tsuikin from other lacquer techniques is the staggering number of these colored layers - often exceeding one hundred alternating strata of vermilion, black, and sometimes gold. Each layer represents a day's work, as the urushi requires precisely 24 hours to cure under optimal conditions. The chronology becomes embedded in the object itself; holding a finished piece means touching compressed time.

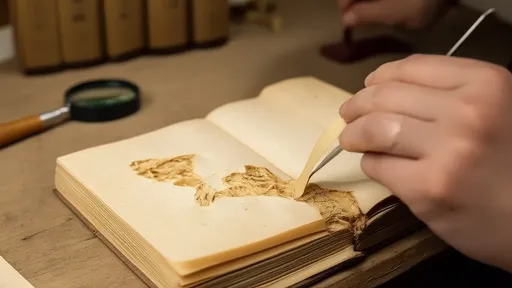

After perhaps half a year of daily layering, the lacquer block reaches its final thickness - usually no more than a centimeter despite containing those countless strata. Now the carving begins, conducted with specialized tools that must be sharpened constantly to maintain the razor edge needed to slice cleanly through the hardened lacquer without chipping. A master carver can tell precisely how deep to cut by the subtle resistance change as the tool moves through different colored layers.

The designs emerge gradually as the artisan reveals the hidden chromatic geography within the lacquer block. Traditional motifs include peonies, chrysanthemums, flowing water patterns, and scenes from nature - each element carefully planned to showcase the maximum color contrast between layers. The precision required borders on supernatural; a cut one millimeter too deep ruins months of accumulated work.

Weather dictates everything in this craft. The ideal workshop maintains 70-80% humidity at 25°C (77°F) year-round - conditions that modern climate control still struggles to replicate perfectly. Many masters still prefer working only between May and September when nature provides the optimal curing environment, following rhythms established centuries before hygrometers existed.

The finishing process involves multiple rounds of polishing with increasingly fine abrasives, from powdered deer horn to fine charcoal, before the final application of translucent lacquer that brings out the depth and luster. A properly finished piece appears to glow from within, with carved patterns that seem to float in three dimensions as light plays across the layered colors.

Contemporary masters like Living National Treasure Kitamura Takeshi have pushed the boundaries further by incorporating up to 300 layers in some works, creating unprecedented depth effects. Yet even these modern innovations adhere strictly to traditional material purity - no synthetic substitutes can replicate urushi's unique properties. The lacquer must come from trees at least ten years old, tapped carefully during specific summer months.

Collectors worldwide prize these objects not just for their beauty but for their incredible durability. Properly cared for, lacquerware becomes more beautiful with centuries of use - the material actually growing harder over time as the urushi polymers continue cross-linking. Museum pieces from the 15th century often appear freshly made, their colors miraculously preserved.

Perhaps the most profound aspect of this craft lies in its philosophical dimensions. The necessity of working slowly, of accepting that some processes cannot be rushed, stands in direct opposition to modern manufacturing mentality. Each piece embodies wabi-sabi principles through its imperfections - the barely visible tool marks that prove human rather than machine creation.

Apprenticeships still last a minimum of fifteen years, with students spending the first five years only preparing materials and bases before ever touching carving tools. This extended training period ensures not just technical mastery but the development of what masters call "lacquer vision" - the ability to see through layers before they exist, to hold the finished design in mind while applying the first coat.

The future of this art form remains uncertain despite its UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage status. Few young people today can commit to the decades-long mastery required, and the increasing rarity of skilled urushi gatherers threatens the material supply. Yet the pieces being created now - each one requiring nearly a year's concentrated effort - may well become the heirlooms of future centuries, carrying forward this remarkable conversation between human creativity and the patient unfolding of time.

In an age of mass production and disposable goods, Japanese stacked lacquerware stands as a defiant testament to what hands can create when granted sufficient time and respect for materials. The layers accumulate like pages in a visual diary, recording not just artistic vision but the very days of their making - a hundred sunrises captured in vermilion and gold.

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025