In the hushed conservation labs where time seems to stand still, a delicate ballet unfolds under magnifying lenses and specialized lighting. Here, conservators engage in what might be considered one of the most meticulous forms of art restoration – paper pulp infill for worm-damaged historical documents. This isn't merely repair work; it's a dialogue between modern science and centuries-old craftsmanship, where every fiber placement matters at a millimeter scale.

The process begins with what conservators grimly call "mapping the damage." Each wormhole in an ancient Buddhist scripture or Ming dynasty ledger tells a story of its own – the angle of penetration, the thickness of paper layers disturbed, even clues about the insect species responsible. Modern multispectral imaging creates topographic maps of these damages, revealing subsurface fiber disruptions invisible to the naked eye. Only then does the real work commence.

Creating the perfect pulp requires alchemical precision. Conservators source contemporary papers with fiber compositions matching the original – perhaps hemp from Anhui province or mulberry bark from traditional Korean papermakers. These are beaten into suspension with deionized water, adjusted for pH balance, then tinted with natural pigments to blend seamlessly. The real magic lies in the viscosity control; too thin and the pulp won't bridge gaps, too thick and it obscures original ink strokes.

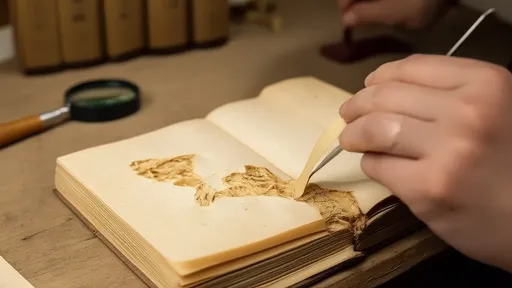

Application resembles microsurgery more than traditional paper repair. Using capillary-action pipettes under stereo microscopes, conservators introduce droplets of prepared pulp into each cavity. The surrounding undamaged paper acts as a natural mold, guiding fiber alignment to mimic the original sheet's formation. Multiple ultrathin layers build up gradually, sometimes requiring a day's work for a postage stamp-sized area. The patience required would make a medieval scribe nod in approval.

What truly astonishes is the post-application refinement. While the pulp is still slightly damp, conservators use micro-spatulas thinner than human hair to tease fibers into perfect alignment. They might employ ultrasonic misting to relax specific areas for adjustment. The goal isn't to make damages disappear entirely – ethical conservation maintains some evidence of age – but to stabilize while preserving readability. When done properly, the repaired areas become chemically and physically compatible with the original for centuries to come.

Recent breakthroughs have elevated this craft further. Nanocellulose additives now allow pulp bridges as thin as 15 microns – about a fifth the thickness of typical copy paper. Some institutions employ spectrophotometers during tinting, analyzing paper color across multiple light spectra for undetectable matching. There's even experimentation with enzyme treatments that encourage repaired areas to "age" chemically, preventing obvious contrasts decades later.

The philosophical implications run deep. Each millimeter-scale repair represents a conscious choice about how we preserve cultural memory. These techniques allow future scholars to study original texts without interference from restoration materials, while giving current generations the privilege of reading words that have survived centuries against all odds. In an age of digital everything, there's profound meaning in maintaining physical connections to handwritten wisdom of the past.

Perhaps most remarkably, this tradition continues evolving. Young conservators now combine these time-honored techniques with computational analysis of paper fiber patterns, creating predictive models for ideal repair approaches. What began as a practical solution to insect damage has blossomed into an interdisciplinary art form – one that honors both the fragility and resilience of human knowledge across the ages.

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025