The Mongolian horsehead fiddle, or Morin Khuur, stands as one of the most iconic musical instruments of nomadic culture. Its distinct shape, adorned with intricate carvings, carries centuries of history, spiritual significance, and artistic mastery. Unlike many Western string instruments, the Morin Khuur is not merely a tool for music—it is a vessel of storytelling, a bridge between the earthly and the divine, and a testament to the craftsmanship of the Mongolian people.

At the heart of the Morin Khuur’s design is the horsehead, meticulously carved atop the instrument’s neck. This is no arbitrary choice. The horse holds sacred status in Mongolian culture, symbolizing freedom, endurance, and the soul of the steppe. The craftsmanship involved in shaping the horsehead varies from region to region, with some artisans opting for highly realistic depictions while others embrace abstract or stylized forms. The wood, often sourced from local trees like pine or larch, is treated with reverence, as the carver imbues each stroke with intention.

The body of the fiddle is another canvas for artistic expression. Traditional motifs—such as the “khiimori” (wind horse), flames, and endless knots—are frequently engraved into the wood. These patterns are not merely decorative; they carry deep symbolic meaning. The wind horse, for instance, represents prosperity and good fortune, while flames signify purification and spiritual energy. The endless knot, a recurring element in Mongolian and Tibetan art, embodies the interconnectedness of all things—a philosophy central to nomadic life.

Beyond its visual beauty, the Morin Khuur produces a sound that is hauntingly evocative. The two strings, traditionally made from horsehair, resonate with a timbre that mimics the natural world—whinnying horses, howling winds, and the vast, open landscapes of the steppe. Musicians often describe playing the Morin Khuur as a form of communion with nature and ancestors. The instrument’s voice is not just heard; it is felt, vibrating through the player and listener alike.

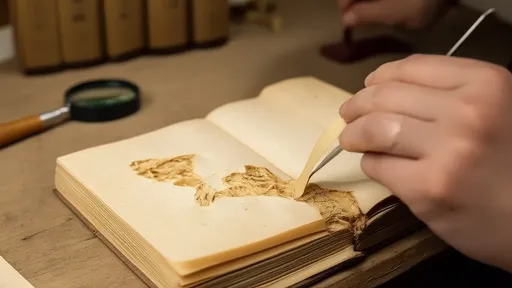

The process of crafting a Morin Khuur is a sacred tradition passed down through generations. Master luthiers, often belonging to families with centuries of experience, approach their work with a near-spiritual discipline. Each step—from selecting the wood to tuning the strings—is performed with ritualistic care. Some craftsmen even whisper prayers or blessings into the wood as they carve, believing that the instrument will carry these intentions into the music it produces.

In contemporary times, the Morin Khuur has transcended its traditional roots, finding a place in global music. Modern musicians experiment with its sound, blending it with electronic, classical, and even rock genres. Yet, despite these innovations, the essence of the instrument remains unchanged. Whether played in a yurt on the Mongolian plains or on a concert stage in New York, the Morin Khuur continues to tell the story of a people deeply connected to their land, their history, and their spiritual beliefs.

The preservation of Morin Khuur craftsmanship faces challenges in the modern era. Mass-produced versions, often lacking the intricate carvings and spiritual depth of traditional instruments, have flooded markets. However, efforts by cultural organizations and master artisans aim to keep the authentic tradition alive. Workshops, apprenticeships, and festivals celebrate the art of Morin Khuur-making, ensuring that future generations inherit not just an instrument, but a legacy.

To witness a Morin Khuur being played is to experience a piece of living history. The musician’s bow glides across the strings, summoning melodies that have echoed across the steppes for centuries. The carved horsehead seems to come alive, its silent neigh joining the music. In that moment, the past and present merge, and the listener is transported into the heart of nomadic civilization—a world where art, music, and spirituality are inseparable.

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025